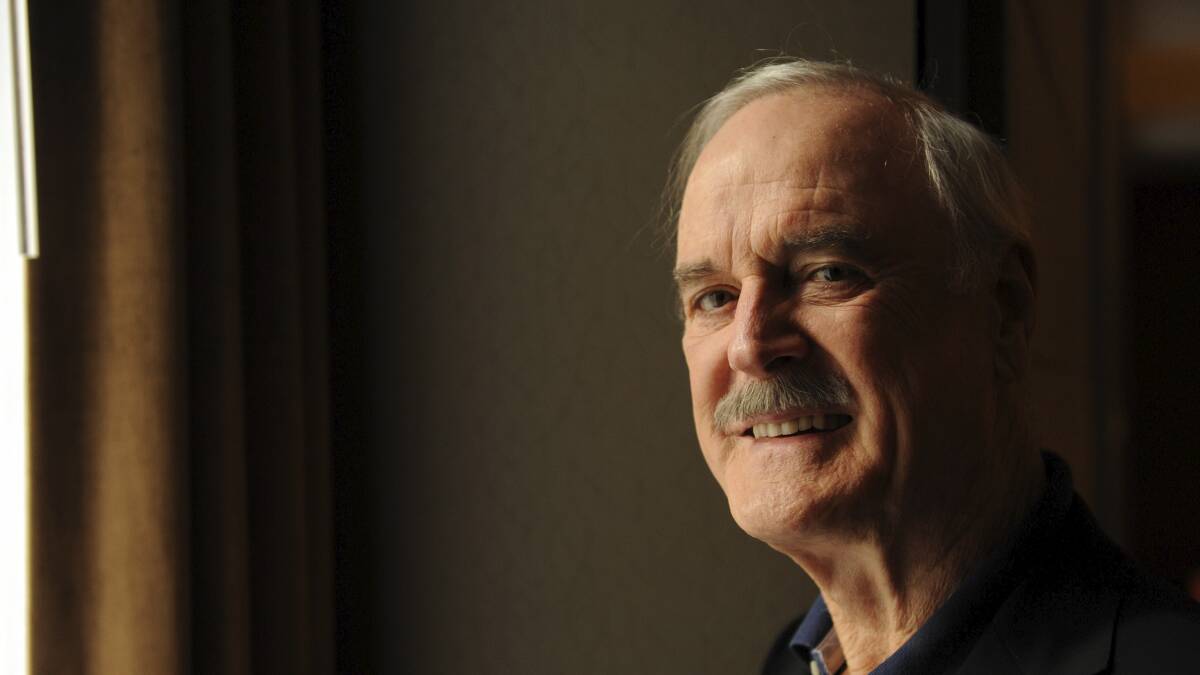

If I achieve nothing else this year, I can say I made John Cleese laugh.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

At the start of the interview, I said that I told an intern I was interviewing John Cleese and the 22-year-old replied, "Who's John Cleese?"

It took a couple more hints - mention of the comedy troupe Monty Python drew a blank, then recognition started to dawn on the intern's face when I mentioned Cleese's sitcom Fawlty Towers - "Oh, the tall guy? I used to watch that with my dad."

Luckily Cleese was not offended: he burst into laughter, then went into a fabled story about the stages of a Hollywood career.

"Let me see if I can get this right. The first thing was: get me a comedy actor. Next one is: Get me John Cleese. The next one is: Get me a John Cleese type. And then the last one is: Who?"

Cleese is coming to Canberra with his daughter Camilla for An Evening With the Late John Cleese. Since he's clearly not dead yet, like the man in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, why that title?

"Well, I just thought it was a nice conceit that I had died recently. I was reporting back from my experiences because most people would be interested in what I'd been through, you know?

"So I make up a bit of the usual rubbish, but I don't yet know what I'll be doing because over the years I've developed probably four to five hours of pretty funny material. I try and put some new stuff in every time, but you don't try everything new because ... you want to have some stuff in there the audience is definitely going to like, and until you've played new stuff to audiences, you don't know how much they like it."

What the audience definitely does like is the Q&A session in the second half of the show: "There's something about that that people just like even more than the scripted bits ... I don't understand it."

Also popular are the film clips.

"They all love the silliest thing we ever did which is called The Fish Slapping Dance ... it's extraordinary how people can see that for the 50th time and still laugh. What I've noticed, it's often the silliest things that people go on laughing at. If there's some point to the humour, then in some strange way it tires, it fades a bit more than the completely stupid stuff."

Cleese acknowledges there's a certain generation gap when it comes to recognition.

"Yeah, well, it's very funny. I mean, if I go to see a doctor in America, the doctor knows who I am. Nobody else in the office has a clue."

How does that make him feel?

"That doesn't seem to affect me very much because I get plenty of offers to do things and the thing is, I'm not affected by wokery because the audience that I get have bought tickets because they like me.

"They don't think, 'I can't stand that bastard. Let's buy six tickets,' you see, so so they're preselected to like me and also to like the sort of humour that I do - so I never get anybody that's offended or walking out because they are people like me."

Back in Monty Python's heyday, the comedy troupe's biggest controversy was probably the religious satire Life of Brian (1979), which was banned in some countries and led to protests in others by some religious groups on the grounds it was blasphemous.

Now some of Python and Cleese's work and opinions are being criticised from the other side of the political spectrum as being offensive and dated.

Since he brought up the subject, why does he think "wokery" - or political correctness, or whatever you want to call it - is such a big issue?

"I don't know. I have a friend who thinks it's a way of distracting us from the really important things that are going to end the planet. But it happens now and again. You get ideas out there, particularly in academia, and everyone gets very, very excited about them. And then somebody points out that they don't work and it all goes away."

Cleese says, "It's very strong in the universities, particularly in America, but it's all based on ideas called postmodernism, where people get an interesting insight and then think is the explanation of absolutely everything. Then they say, well, every single thing that happens anywhere on the planet has to do with power. No, it doesn't. There's a lot of truth, but it's not the only truth. But they behave as if it's the only truth."

It's not the only problem Cleese sees nowadays.

He thinks that about 1990, "the BBC became a bureaucracy and they're producing very little comedy that's any good now".

"We had a director general who was a data man and who had no sort of gut instincts, and I think he thought that it was best if the BBC ran as a bureaucracy. And there's no point having bureaucrats in charge of comedians because they've no idea how creativity works. That's why they're bureaucrats."

And how does creativity work?

"It's not a hard question because I've written the book about it," Cleese says. Indeed he has: it's called Creativity: A Short and Cheerful Guide and, he says, it takes about 45 minutes to read.

Many books about creativity are written by psychologists, Cleese says.

"And they will say, if you moved a lot when you were a child, if your parents moved house a lot, you'll tend to be more creative.

"Well, that's very interesting but it's not useful unless you can move backwards in time ... And what I say is, all really creative and really new stuff doesn't come from the logical part of our mind, you know, the logical or the analytical part."

"Creativity comes from our unconscious, and we've got to learn how to work with our unconscious, which you can't order about, you have to coax it and trick it a little bit like, you know, when you forget a name and you try and think what it is and two minutes later it pops in your mind - your unconscious has given you that name, but it's not given it because you just ordered it to, it just took its time.

"So if you learn to work with the unconscious, I find that creative work becomes much, much easier. But the only thing I insist on is time, because if you're under time pressure, you will always slip into stereotypical ways of thinking."

Cleese also likes to collaborate when writing.

"Oh, now I'm writing a lot of stuff with my daughter who seems to complement me, and I complement her in a very good way. I like that because you often think when you're working with someone else that you get to somewhere that you would never have got on your own."

They're working together on a new Fawlty Towers.

"Yeah, we've only had a few days on it so far. We've really made very little progress, but it'll be completely different to the original. Probably set in the Caribbean with a multicultural cast ... Nothing to remind you of the original at all.

"We've also written a comedy about Hollywood lookalikes. You know, the guys who stand on Hollywood Boulevard pretending. And the idea, which is not ours but is brilliant, is that the lookalikes are played by the originals. So Arnold Schwarzenegger plays his own lookalike, and we've written a script and it's very, very good.

"But of course, now there's a writers' strike, so nobody knows when it'll happen."

He's also adapted Life of Brian for the stage which will debut in London. Unlike Eric Idle's Spamalot, adapted from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, it isn't a musical.

"Life of Brian has got too many important ideas in it. And if you start to do nice, bouncy, happy songs, it would slightly trivialise it."

He isn't collaborating with the surviving Pythons (Chapman and Jones have died).

"We had a meeting about it pre-COVID ... I was assuming that Michael [Palin] and Eric [Idle] might want to and they didn't. We had a full meeting. Eric was there on Zoom and none of them wanted to do it. So I've taken it off and I've changed it quite a lot because I wrote quite a lot of the original."

He doesn't feel tied down or like he's messing up other peoples' work and he's changed the ending.

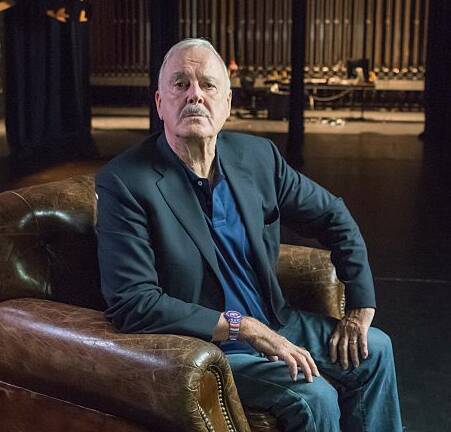

!["I feel more at home here [Australia] than I do in London." Picture Getty Images "I feel more at home here [Australia] than I do in London." Picture Getty Images](/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/Z4Q6sUEHdcmw72MBPYgZkU/92fa42d8-85b6-4588-8007-5b705db94943.jpg/r0_0_531_763_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg)

"I don't think that watching people on crosses singing after 44 years of being able to watch that, I don't think we should just reproduce it."

What about Always Look on the Bright Side of Life?

"Well, I think we'll have the song in there because everybody wants it in there. One person said to me, you should have the song because the audience would expect it. I said to them, 'When did Monty Python do things because the audience would expect it?'"

But he will include it.

"Of course, people would miss it..."

Monty Python - comprising fellow Brits Michael Palin, Terry Jones, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman and American Terry Gilliam - created television, movies, books and records. They were influenced by everyone from the Goons to silent comedians like Buster Keaton but added their own blend of the intellectual and the nonsensical.

"Oh, it was a good team, it had people who do different things very, very well. Gilliam didn't really, as far as I remember, ever contribute to the writing. But his animations, nobody else could have touched him and they worked incredibly well.

"Eric was extremely gifted in jokes. He was a very good impersonator and wonderful at lyrics.

"Terry [Jones] and Michael were absolutely prolific, and Michael ... [has] got a touch of genius there with his ability to create character.

"Jonesy was very good at ideas, you know, like things like, 'What have the Romans ever done for us?' ... So some of the best sketches were thought up by Terry and then were dialogued by Graham Chapman and myself. Chapman and I were slightly old-fashioned, but we did very crazy, very funny sketches which fitted in very well. And Graham was a very, very strong performer ... so everyone was good at different things."

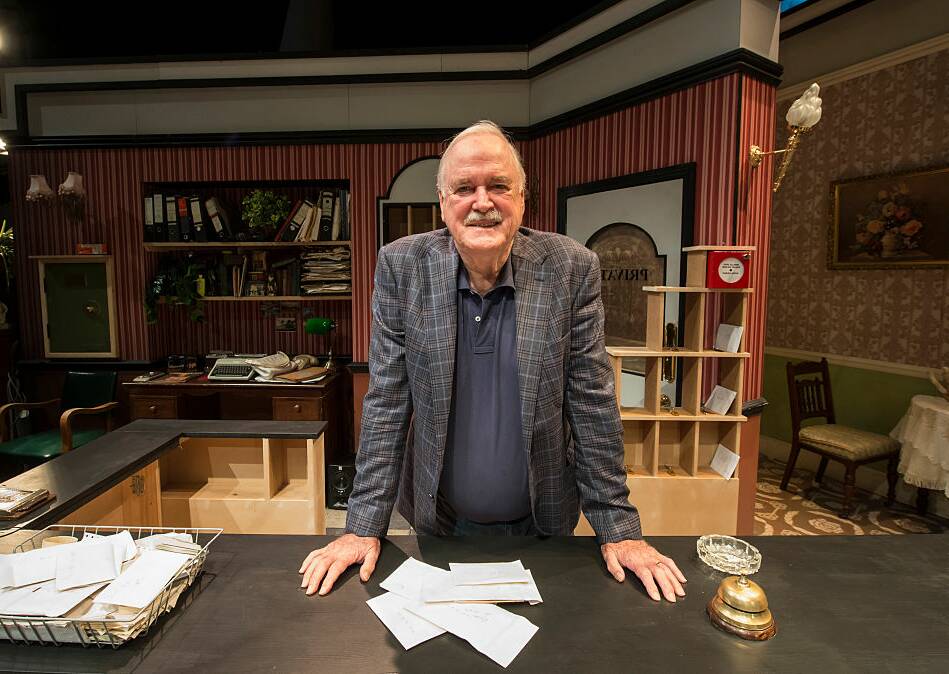

So will Cleese be playing Basil in the rebooted Fawlty Towers?

"Yeah, I play Basil ... It's just a glint in the eye [and]... not much more than half an idea at the moment."

Fawlty Towers - inspired by an eccentric and hostile hotel keeper Cleese endured - was adapted for American TV three times and failed each time.

"The problem was ... there were very, very few people in charge of television or film who knew what they were doing.

"But that's really been my experience for ever and a day that very people know what they're doing. And three times the Americans said, 'No, we know what we're doing.'"

The last time, he was told only one thing had been changed.

"I said, 'What is your change?' And they said, 'We've written Basil out.' This was the great idea of the executives about how to do Fawlty Towers, which is to remove the main character. And this is the kind of stupidity that I've been up against and all comedians have been up against because it's a very specialised thing. And so many people think they understand it when they don't.

"We only understand it a bit, but they don't understand it at all."

The original 12 episodes of Fawlty Towers ranked first on a list of the 100 Greatest British Television Programs drawn up by the British Film Institute in 2000 and, in 2019, it was named the greatest British TV sitcom by a panel of comedy experts compiled by the Radio Times.

"It's because it was very good. And we worked very hard on it. And we also played the comedy much faster than they usually play television comedy because I told the actors, who were stage actors mainly, I said, 'Don't wait for the laughs. You've got a microphone three feet from your head. The audience at home can hear it, so don't wait for us. Play it faster.' I think that's why it was so successful."

There's been a stage version too, but he was not involved.

"No, no. It is extraordinary. They've been doing it for over 10 years. A few years ago, they made at least a million pounds a year and they've never paid [co-writer] Connie Booth or myself a penny."

How could they get away with that?

"Because most of English law is a f--k up.

"They changed the w of Fawlty Towers to a u - Faulty Towers. Just to disguise the fact that, you know, it was mildly connected with our show and they were using our characters and plot points ... But the British law gave us no protection at all."

Although he doesn't enjoy flying ("because at 83 years of age and six foot five, it's such a miserable experience"), Cleese is looking forward to his Australian tour and says he's always liked it here.

"Terrific. Terrific. Last time I was in Australia, I walked out, I was in a hotel on The Rocks in Sydney and I thought, 'It's very strange, but I feel more at home here than I do in London.'"

Why is that?

"I can't explain it, I don't know. I mean, London has changed a lot from the '60s ... it's a much less intelligent place than it used to be. There used to be a wonderful audience, a London audience for good plays. It doesn't exist anymore. I've been told that by all the promoters, you know."

Last time he was in Canberra he stayed at the hotel at the zoo and hopes to again.

"I thought it was fantastic ... last time I was there, I petted the the cheetahs. The zoo guys were keeping them quite busy feeding them, but I was allowed to pet them, I've always loved cheetahs."

He's also got a soft spot for hyenas.

"I think there's something terribly good about going to zoos and looking at these extraordinary creatures - I think it kind of puts us in touch with something important that we don't normally think about."

Cleese also has a fascination with near-death experiences.

"The stuff that's out there at the moment is absolutely extraordinary and really fascinating. The trouble is it frightens scientists because they can't really explain it, so they sweep it under the carpet."

While he acknowledges "there's a lot of rubbish" written about the subject, Cleese says there are better sources.

"For example, there's a book called After and that's about near-death experiences. And if you start reading that, it's really quite extraordinary when you realise all the evidence that's out there [about] out-of-body experiences, all these things and the scientists, they can't explain it. They talk rubbish. They say, 'Oh, you mean people on drugs and hallucinating' whereas these experiences are far more clear than ordinary life and all experiences under drugs are less clear than ordinary life."

John Cleese's life has been anything but ordinary. And he's still very much with us and shows no signs of leaving any time soon.